ROBERT GRANT

Interview

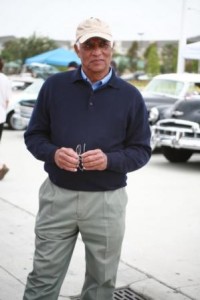

Robert Grant has enjoyed a long career in film and video production, first as a cinematographer, then as a producer

As a media producer for Hughes Aircraft, and later, as Manager of Visual Media for Hughes Corporate, Robert garnered awards with videos touting the company’s many products, most notably, showcasing the history, science, manufacture, and many uses of communications satellites, a technology invented by Hughes scientists., writer and director of documentary and informational films and videos.

Robert founded what he likes to call a media co-operative, RGO Media Associates. Along the way, he taught cinematography and film production at the UCLA Film School, where he has an MFA Degree.

PJS – Congratulations on the debut of your new book! What is the title and what’s it about?

RG – Thanks, Pamela. The book is called, “What Many Men Desire.” The title comes from the scene in Shakespeare’s “The Merchant Of Venice” in which Portia’s father is essentially auctioning her off to the first nobleman able break a simple code! The swain has to guess which of three “caskets” he should open to find the chit that will earn him Portia’s hand (one hopes that wasn’t the norm in the 16th Century!!). The Moroccan Prince makes the obvious—and incorrect—choice, saying: “Let’s see, once more, this saying graved in gold./ ‘Who chooseth me shall gain what many men desire.’/ Why, that’s the lady, all the world desires her…” He got the hook.

The title plays into my book’s theme because the book is very much about choices, and about appearances vs. their underlying reality. It’s the story of Audrey, a young and beautiful woman apprenticing on Park Ave. She has a passion—and the talent—for the fashion business. But she’s multi-ethnic—African-American, Cherokee, white, and it’s 1936! So she’s passing for white in her work life because she knows she won’t have any chance if she’s honest about her ethnicity.

A gentleman invites her to go with him, as his “assistant,” on a voyage to England on the brand new Queen Mary. She’s eager—it’ll get her to the heart of haute couture—London and Paris. On the ship, she learns a lot about life, she falls in love, and she edges into danger, as her “gentleman” turns out not to be what he seems.

PJS – Where can people find your book?

RG – I’m pleased to say that it’s available on Amazon, both as a paperback and as an e-book. And there’s a website where you can read the first two chapters.

PJS – Why did you decide to self-publish rather than look for publishers and/or agents?

RG – Well, I can’t say I’m not looking for those things; I’d still be happy if an agent or a publisher—or both!!—took an interest in the book. But making that happen for an unknown writer is the closest thing to impossible. It’s the old, but still quite real, Catch 22: If you have a name as an author, the publishers and agents will line up at your door, hoping to profit from your fame. If you’re unknown, you could be another Stephen King or J.K. Rowling, you can’t get anyone to take a serious look at your stuff.

Publishing through Amazon’s CreateSpace site (which is very affordable, by the way) gives me the chance to build a readership that isn’t moderated—and limited—by the established publishers. Then, if it gets some traction and starts selling, a publisher might become interested and I’d certainly be willing to talk.

PJS – What did you get from working with a writing group?

RG – I found that a writers group was indispensable, on many levels. First, of course, is the feedback—they tell you what you’re doing wrong. I was doing quite a lot wrong but the group straightened me out. Maybe it’s not true for everyone but, for me, trying to judge my own work without getting it in front of other, critical eyes, is a huge mistake. The other thing they did was to help me finish, by encouraging me to keep working at it. They come up to you and ask, week after week, “How’s the book going? How’s Audrey doing?” After a while, you have to have something new to say.

PJS – You’ve written scripts as well as fiction prose. Why did you go the book route for “What Many Men Desire”?

RG – The question implies that The Big Screen was always my goal for “…Desire,” and I’d be lying if I were to say I have no interest in that. But I’m not sure that was ever my first goal. When I decided I needed to take a stab at writing it, I always thought of it as a novel. But I’ve been surprised at the many reactions I’ve had suggesting that people see it as a movie; I guess that’s a reflection of my writing background. Most of the writing I’ve done, over a long career making informational movies, has been for screens, although those screens were mostly small in size and in number. So I guess it means I automatically tend to write scenes that have strong visual content. That’s a good thing, isn’t it?

PJS – Absolutely a good thing! What other writing projects are you working on now?

RG – I was surprised to discover that I can easily see a sequel to “…Desire” and I’m sketching it out. In putting Audrey on a boat to England in 1936, I’ve sailed her into the teeth of a brewing conflict in Europe that soon erupted into World War II. I’m curious to know how she handles it.

PJS – You travel a lot…how does that influence your writing?

RG – Well, as you know, every influence from outside our culture is seed stock for our imaginations. Those influences open our eyes and sharpen our minds, and when you’re creating a story, useful ones can sort of drop into your hand, like an apple falling from a tree. They help shape character and, of course, they can help a writer create a sense of place, and of atmosphere.

PJS – What did you learn while writing this book that might help other writers?

RG – I don’t know that I’m in a position to teach anyone a thing about writing but there are a few specific things—Tips & Tricks—I’d be willing to throw out as suggestions for someone starting out. The most important derives from another old saying, a cliché because it’s so true: If you want to be a writer, you have to polish a chair for at least four hours a day. There’s no way around this one.

Next—and this tops the list in importance—when you’ve “finished” and you feel it’s ready for prime time, do not put it out for general consumption. Instead, give it to an editor. Not to a friend who writes well–to an editor; your book will be much the better for it. It will probably cost you some money, and it should, because, if you find a good one, he or she will make a huge contribution to your book. The lesson here is: Unless you’re very unusual, you’re a lousy editor when it comes to your own work. You simply will not be able to see its flaws (which you are pre-disposed to believe do not exist).

One other thing. I caused myself a lot of trouble—and embarrassment—because I have too much confidence in my spelling. After the countless readings and re-readings of my work, I was certain I had caught all the little typos and other uglies. I’ve simply never developed the Spell Check habit because, before this, I never seemed to need it. Big mistake!! A novel is a mountain of words (about 106,000 in my case). And, good writer though you are, it’s a near certainty you haven’t put them all down correctly and it’s ridiculously easy to miss some of the errors. Save yourself some grief and use Spell Check.

PJS – And with the wisdom of your own long career in visual media, what do you think are the three most important things for content-creators to know?

RG – That’s easy. One: Know what you’re talking about. Two: Know what you’re talking about. And Three (you guessed it): Know what the hell you’re talking about.

PJS – How did you get started in Media?

RG – I suppose that, without my quite realizing it, it was in my blood. My dad was a singer and actor, and always interested in radio and the theater and the movies. When I was about 11 or 12, he had a weekly entertainment show that he wrote and produced, on a small radio station in Pasadena. Lots of corny exchanges like: “Hey Bob, have you heard that new Bing Crosby song?” “Yeah, Al, it’s a real corker. What do you say, we give it try?” I was witness to the process of script writing and casting and all the rest, and was there in the studio during many of the broadcasts—they were all live.

At one point, my dad was on the cusp of a real career as an actor; he has some lines in a crucial scene, opposite William Holden, in the original “Golden Boy,” so you know he was serious. Racial issues turned all that to dust in the end but I suppose I was bitten. I never intended to follow him into media but one thing led to another and, before I knew it, I had a BA in Theater and was enrolling in the UCLA Film and Television MFA program.

PJS – Tell us a bit about the most interesting projects you worked on?

RG – Early in my career, my ex-wife and I made a trio of movies about Mexican folk artists. We shot them on location in Mexico City and in Oaxaca. Each one was about a different artist. They were each well known throughout Mexico—one had an international reputation—but they all lived simply, in circumstances that any of us would equate with poverty. Yet they were great artists, and proud and happy people. Delving into their artistic lives, and their family relationships, was easily the most interesting work I’ve done in filmmaking. After that, it’s probably the movie you and I made together, one our awards films at Hughes, about the clever and successful attempt to rescue and revive an errant communications satellite, by slinging it around the moon several times. You don’t get to see something like that every day.

PJS – You exec produced my award-winning comedy short ‘It’s a Jungle Out There” [thank you] with the animal actor – a python. And then you – did a musical! – also an award-winner. What did you like most about those annual shows?

RG – Well, of course, what was great about those little movies was that we had the chance, rare among the assignments we usually got, to let our imaginations run a little bit free. We had fun, got to work with many of our favorite people, produced some quite good films, and entertained and informed their intended audiences, all on somebody else’s budget. What’s not to like?

PJS – The 1990s was a fine time for science advancements and you were in that field. What did you work on/film then that has changed the most today? [My example is the 18-wheeler with arm-thick cables the first HD setup required. We were going to do it for the Geneva Motor Show, remember? And the transfer from film to HD was something like $700/frame. Or was it $7,000?]

RG – There was a change in satellite technology that the average Joe or Jane has no concept of, but it was a true paradigm shift that greatly increased the power available on a satellite, and it happened in the labs at Hughes. At first, communications satellites were these big, blue cylinders, up to about 15 feet across, with antenna clusters sprouting at one end. The cylinder turned slowly as the satellite orbited in space, to provide stability, essential for keeping the antennas pointed the right way. The cylinders were covered in solar cells but they had a built-in limitation. Only about 1/3 of the solar cells faced the sun at any one moment, the rest were in shadow, pointing out into space as the big cylinder turned. This limited the number of transponders the satellite could support and, in the communications satellite biz, transponders are your stock in trade. They kept making the cylinders bigger and bigger because the bigger they were, the more solar cells you could put on them. When they couldn’t make them any longer, due to launch vehicle limits, they telescoped them so they could stretch them out when they got into orbit. But they were pushing the envelope to the max.

Finally, the Hughes engineers figured out how to build a satellite that didn’t need to spin—it’s called three-axis stabilization. They put flat solar panels on them that were folded for launch and stretched out, accordion-like, in orbit. These satellites doubled and tripled the available power, bringing down the cost of space-borne transponders and enabling such technologies as satellite television.

Of course, the big change in our industry has been the digital revolution. At the same time the computer chip was transforming the business world—turning typewriters into doorstops, and putting phones in our pockets that allow us to communicate instantly—and virtually for free—with people anywhere in the world, it was also changing all aspects of image capture and handling and presentation. First came the shift from film to tape. Sprocket holes—remember them? Random access editing turned video from a useful, if clunky, industrial tool into the new gold standard for post-production. Then, the old bottleneck, storage, dissolved, which then made videotape obsolete, essentially overnight. Cameras now have hard drives in them! Finally, projection. I went to the movies the other night. It was a multiplex—seven screens—and not a single film projector in the place.

PJS – What projects does your company RGO Media have in the works?

RG – RGO isn’t very active at the moment—I’ve been putting all my effort into writing. We do have one project still in development—“Hearts On Wheels,” about guys who restore old cars, and we’re looking for financing.

PJS – Thank you so much, Robert, and best of luck with all your projects. I look forward to reading the sequel to “What Many Men Desire”. http://www.whatmanymendesire.com/#